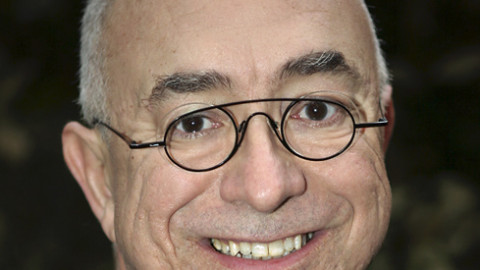

Interview – Heikki Kossi

Finnish foley artist Heikki Kossi is known for his work on Sound of Metal, Ad Astra, The little Prince and The Cave. He has worked as a foley artist since 2001 in feature films, shorts, TV-drama, documentaries and animation films. As a sound designer Heikki has been involved in feature length documentaries and animation. As a director he has made three documentaries.

How did you get started in the film industry?

Back in 90’s I was a professional musician playing upright and electric bass in different roots bands of old downhome blues, jazz and rock’n roll. Afterwards I’ve been thinking about that time and I realised that through the direct body contact with the instrument I learned the feeling of right tone and colour of the sound. You can really feel when sound comes alive. In the late 90’s I started studying radio. I created sounds for the radio features and documentaries in the same way as foley but of course without image. At the end of that study we did few shortfilms and I found out there was a profession called foley artist. I started to investigate the art of foley. In that time there was no full-time professional foley artist in Finland. After I graduated year 2001, I was lucky to start working on animated tv-show which of course needed lots of foley. That show aired weekly and I started to buildup myself professionally.

How did you prepare for your foley work on Sound of Metal?

Well, we started talking about the sound of body resonance with supervising sound editor Nicolas Becker. We both had experience with working with this kind of subjective perspective. Nico with Gravity, and me with Ad Astra. Both films included sounds felt inside a spacesuit and through a spacesuit. With Sound of Metal the great challenge was to go few steps further.

“The first feeling is my guideline through the whole foley process.”

From what point are you usually involved in the production process?

Years ago, when I started out, it was quite usual to start the foley work after the picture lock. Nowadays we already do some scenes or important sounds during picture editing. Or we even start the whole process a few versions before the locked version. I feel that it’s not much extra work, as long as there’s a good plan between the picture and sound departments. Everybody really needs to pay attention to proper EDL’s etc. The foley which is done during earlier cut versions helps the editing, and usually the edit stays pretty much the same. And I always do these early sounds like they are the final ones.

Where both the director and the sound designer heavily involved in the foley recording?

Yes, indeed. When we started recording footsteps, Nico and director Darius Marder where in Paris working on the film aswell. So I was able to just call them in and have creative talks. They were really open to that, and we had really nice discussions about the aesthetics of the film and colours of the needed sounds. Nico has strong background as a foley artist himself, which made these moments even more special. We worked with reels on this film, and after finishing a reel I sent it to them immediately for listening. Also I wanted to send them the first recordings of these inbody sounds, to check out that we were on same track. I felt that there was a lot of love during this process.

Did you do full foley for the whole film, or where certain parts not needed because of the deafness of the main character?

Sound of Metal required full foley work with a very specific planning. During the picture editing process picture editor Mikkel G.E. Nielsen and Nico were collaborating closely. We had really specific plan of when to go inside Ruben’s head and when to go back to realism. So we didn’t make sounds double, “just in case”. There is quite a big misunderstanding that with bigger films you just foley everything. Especially with bigger projects there is always a kind of rule: don’t do anything we don’t need. Or with layers: there is no need for layers which sound the same.

Did you take music and tonality into account during the foley recording of Sound of Metal?

Or was this created in sound design later on?

A bit, yes. The moment when Ruben is playing drums and hardly hears anything, I used headphones to listen to the rhythm of the music while doing foley for his body resonation. He didn’t hear music, but his body felt the resonation of the stage. We had a plan, and in the end we put the elements together. Sometimes it comes out as planned, sometimes it creates something new.

You were expected to create foley that in a way was “unheard” of ever before. Was this intimidating to you?

No, not at all. Maybe ten years ago it would have been intimidating. Through the years I’ve followed my instincts, and hit the right “note” more than once so that gave me good selfconfidence. At the same time I needed to be humble, and respect the story and the collaboration with Darius and Nico. One thing which always helps are the creative talks with the supervising sound editor, and preferably with the director as well, if possible. When talking about sound, the moment you have to start out comes pretty quickly. You just need to start working and create everything from scratch. Then it’s important to continue the talks and have constructive feedback and find the correct way to go.

You used a “stethoscope” microphone to record parts of the foley.

How did that come about and how did you construct it?

With Nicolas Becker, we talked quite a lot about body resonation and ways to record it. We both experimented with it in earlier projects. As already said, Nico with Gravity, and me with Ad Astra. With those projects we used mainly contact mics, at least I did, to record resonation and touches of different objects through a space suit. Nico wanted to go deeper into this idea and introduced me the stethoscope microphone. He gave me some links to find the instructions of how to build it. With the help of my friend, who is music enthusiast and electrician, we built one. With stethoscope microphone it felt more organic and real compared to using contact mics. We really felt that we had direct access to feel blood running through veins.

Did it require a different approach in your foley performance?

Basically not, because like usual, it was a question of creating sound sync to the picture. I was holding the microphone in my hand, and the sensor was in contact with my body. It just took a bit of time to learn how to hold it. But it’s the same thing with every prop or shoes. One difference was that I needed to use headphones to hear the sound I was working on. Sometimes I was playing back both the sound I was creating and also sounds which are already there. Depending on what I needed it to fit with.

Which scene in Sound of Metal was most difficult for you to do? And why?

Well I don’t know, the most challenging scene probably was the one where Ruben breaks his studio in Airstream. That scene included quite a lot of work with details and textures. One of my favourite scenes is the one when Ruben and the deaf boy are communicating on the slide of kidsplayground. Creating the right kind of textures and perspectives took a bit time.

How many recording days did you have on Sound of Metal?

Ten days.

Was that different than the amount of time you’re used to?

Sound of Metal was a low budget film, luckily the producer saved some extra money for sound post. So ten days was basically pretty a normal amount and we made an efficient plan of how to best use these days. Sometimes there are films with just five days of walking, but it can be also 20 or more for bigger films. It depends so much on the kind of movie and the budget. I always like to say that we do our best to help the film with resources we have.

How do you deal with sound perspectives during foley recording?

We try to record and perform foley as close to the final mix as possible. Working that way I get a better picture of the whole soundscape. Then less explanations are required during recording. When working with interiors we use several mics to mix roomsound into the foley. Exteriors are mostly recorded with one mic, but we are still using eq and positioning of microphones to create the right kind of feeling of perspective. It’s a question of creating the right kind of perspective ánd make it fit with the production sound best. So creating the exact same distance what we see in the picture is not always required.

“I try to record and perform foley as close to the final mix as possible.”

How much do you control your foley props?

Do you leave room for coincidental unexpected sounds?

I try to control the prop as much as possible. But also leaving room for creativity and coincidental surprises. And again, it depends on the sound I’m working on. Sometimes there is need for a clean layer of sound and the “surprise” part comes as an additional and different track. And if there is already something on the fx or production track, sometimes i just create an extra missing layer. Then I try to be pretty specific.

What’s your favourite foley prop and why?

I don’t know. No favourites. I like steps but also everything else.

What’s the most difficult (recurring) sound in films for you to perform?

It’s always such a great challenge trying to fit with the story and emotion. No special sound. Every project is different and there is a need for ability to match with new aesthetics of every upcoming project.

Way to many people see foley as a technical process. What is your view on that?

Foley is acting with sound. It can’t be technical. For me technical means cold. Of course I need to have good enough techniques as a basis for my creative work. But it doesn’t mean that it’s technical. Foley is acting with characters and their emotions. Acting sounds to which they react. Acting means that you try to interpret the feelings to the audience.

Is there a difference between doing foley for fiction films and documentaries to you?

Basically not. And again, it’s like acting. Quite often documentaries have a rougher production track I need to fit, which might cause some more challenges. But at same time, the fact is that documentaries are about real people which can be touching. Every project leaves you something. Fiction and documentary foley are both “walking” for the story.

“Foley is acting with sound.

It can’t be technical.“

Are you at the point in your career where you feel confident in your artistic decisions?

Maybe you can say so. Earlier I was more thinking about “is this what they are looking for” or “does it sound like this in real life?”. Nowadays, I’m more and more interested in manipulating the realism. If it doesn’t work, let’s do it again. Also having good feedback from people I’m working with is important. Everybody needs some compliments every now and then, and we need to remember to give them back as well.

What inspires you in your work?

Inspiring environments with creative ideas from everybody involved. Of course great project helps as well. Personally I have always felt that the biggest reward is when I listen to the final foley track, with all other sounds and I realise that the film has improved. It’s very emotional moment. Not because of me but because of the story.

What three films should every sound designer watch for foley inspiration?

I’m so bad with this kind of questions. But how about these:

– Classical foley but so much character with everything.

– All Coen films has amazing foley and sound design. Foley artist Marco Costanzo is amazing performer. I especially love the sound and intonation of the feet with this one.

Your work has international succes. How did you make the leap to doing big international projects?

Well, some people might call it luck. And another question is, what are big international projects? Does is have something to do with budget? Or story?

You work pretty remotely from Kokkola in Finland. Does this affect your international work?

Basically not. Sometimes there is some co-financing issues which might mean the foley needs to be done in some other country. I’ve been really happy to see that people I’m working with want to work with me and they fight for it.

Knowing what you know now, what piece of advice would you give yourself when you started out in Sound Design?

Watch more films. The classics. Watch films because of the good story.

Be interested in everything. (Well I’ve been :).

Watch a special on the Sound Design of Sound of Metal